A bilingual blog containing the perspective of Ng.Uyên (Wyndi) Nicole NN Duong (Nhu-Nguyen) vung troi tu tuong cua Duong Nhu-Nguyen dien ta bang song ngu Anh-Viet

Sunday, February 27, 2022

flower in a cave

Saturday, February 26, 2022

METAFICTION TIEU THUYET HAU HIEN DAI

https://usvietnam.uoregon.edu/metafiction-trong-tie%cc%89u-thuyet-vie%cc%a3t-nam/

VĂN HÓA XÃ HỘI

“METAFICTION” trong tiểu thuyết Việt Nam?

Published 1 tháng trước

on 16 Tháng Một, 2022

By Dương Như Nguyện

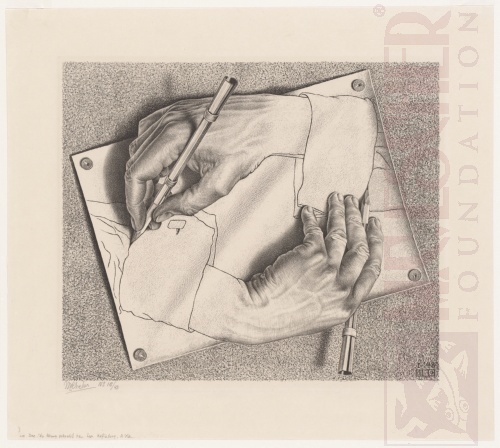

(Bức tranh “Hai bàn tay vẽ lẫn nhau” [Drawing Hands] của M.C. Escher, 1948. Nguồn ảnh: M.C. Escher Foundation)

Wendy Nicole NN Dương (Như-Nguyện)

Câu hỏi mà bài viết này đặt ra là: Có hay không, “METAFICTION”, một nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết mới mà cũ, trong tiểu thuyết Việt Nam? Tại sao không, tại sao có? Từ bao giờ? Bài viết này chỉ nêu câu hỏi và đặt khung cho sự bàn luận, chứ không phải để đưa một câu trả lời duy nhất.

SỰ TIẾN HOÁ (HAY THOÁI HOÁ) CUẢ NGHỆ THUẬT TIỂU THUYẾT

Khoảng năm 1970, William H. Gass, một tiểu thuyết gia và giáo sư Triết người Mỹ, viết cuốn Fiction and the Figures of Life, dùng danh từ “metafiction” để nói đến một trạng thái và thể loại tiểu thuyết trong đó tiểu thuyết gia cắt đứt hay chọc thủng bức tường phân biệt giưã tiểu thuyết và đời sống. Đây là vấn để “ý nghĩa cuà ngôn ngữ” – semantics — rất phức tạp,vì tự nó, dạng tiểu thuyết là “hư cấu” – ý nghiã cuả chữ “fiction,” nhưng nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết tự nó nhắm đến mục đích làm cho nhân vật và thế giới cuả nhân vật biến thành “hiện thực,” dựa trên căn bản cao nhất cuả nghệ thuật kể chuyện/truyện, và nghệ thuật trình diễn: nghệ sĩ phải đưa khán, thính, độc giả vào một trạng thái gọi là “suspended disbelief,” niềm hoài nghi cuả khán, thính, độc giả về sự việc “có hay không” bị treo lên, mất đi, vì khán, thính, độc giả đang bị mê hoặc bởi nghệ thuật mô tả hay trình diễn, đắm mình vào thế giới cuả ảo tưởng, mà lại quá “thật” đến nỗi đám đông tưởng tiểu thuyết trở thảnh “sự thật.”

Gass dùng danh từ “metafiction” để mô tả sự tiến triển cuả thể dạng tiểu thuyết, là một bộ môn văn học nghệ thuật đã trưởng thành qua thời “hiện đại,” đi vào giai đoạn hậu hiện đại (post-modern). Trong thế kỷ 20, các tiểu thuyết gia đã đầy đủ kinh nghiệm lịch sử chính trị xã hội và tinh thông bộ môn sáng tạo để đặt lại vấn đề “tiểu thuyết” – ranh giới giữa“thật” và ảo.”

Hiện nay, metafiction là thể gây khó khăn nhất trên con đường xuất bản để đem tác giả vào thị trường văn chương cuả Mỹ. Hầu như không ai viết metafiction nữa, để dễ dàng kiếm mại bản văn chương – literary agent, và nhà xuất bản. Đã là tiểu thuyết thương mai – commercial fiction – thì không thể là metafiction.

Hiện gịờ, với tình trạng Internet và digital society, có sự tiên đoán rằng dạng tiểu thuyết văn chương được chọn lọc để xuất bản dưới tiêu chuẩn phi chính trị, phi thương mại, rồi sẽ đi đến chỗ diệt vong, và ai cũng trở thành “tác giả,” nói chi đến metafiction.

ĐỊNH NGHĨA METAFICTION

Tôi thấy người Việt Nam bây giờ dịch chữ “metafiction” là siêu tiểu thuyết, siêu hư cấu (có người còn viết bài giải thích theo khuynh hướng này). Theo tôi, đây có thể là một sai lầm về ngữ học, dẫn đến sai lầm về nội dung.

Chữ “meta” có hai nghĩa : 1/ vượt lên trên, đứng bên ngoài; thoát ra khỏi; 2/ thuộc về chính nó, nói về chính thực thể ấy. Chắc vì vậy mà metaphysics được dịch là “siêu hình.” Nhưng thật ra, metaphysics là ngành học nhìn vào tính chất của thực thể (reality), trong khi physics là ngành vật lý, tức là khoa học thực nghiệm nghiên cứu về vật thể (matter). Đứng bên ngoài vật thể (matter) là hành trình nhìn vào tính chất của thực thể (reality), vì vật thể (matter) tạo ra thực thể (reality), nhưng thực thể (reality) không phải chỉ dựa trên vật thể (matter) mà thôi.

Vì thế, metafiction đích thực là tiểu thuyết nói về chính tiểu thuyết, trong đó chữ “meta” có nghĩa là “thuộc về chính nó.”

Một thí dụ của metafiction: nhân vật nói chuyện thẳng với độc giả (thay vì chỉ nói với nhau); hoặc tác giả trở thành nhân vật nói chuyện trực tiếp với độc giả, bước ra ngoài môi trường hư cấu của cốt truyện, hoặc câu truyện kể bên trong một câu truyện khác (truyện lồng vào truyện). Hoặc tác giả bước thẳng vô tiểu thuyết cho độc giả biết họ đang đọc một sản phẩm hư cấu, tức là tác giả đã phá cách tiểu thuyết.

Mội thí dụ khác: trong tiểu thuyết có luôn phê bình và nhận định tiểu thuyết. Tác giả vưà viết tiểu thuyết vừa phê bình luôn tiểu thuyết của chính mình để nhạo báng thế giới nghệ sĩ hay khoa bảng chẳng hạn. Đó cũng là một hình thức metafiction.

Chữ “siêu hư cấu” và “siêu tiểu thuyết ” dùng chữ meta với ý nghĩa “super” thì không đúng. Độc giả có thể hiểu lầm rằng “siêu tiểu thuyết” là tiểu thuyết… khoa học giả tưởng, hạng quá sức “siêu.”

KINH NGHIỆM CÁ NHÂN

Sau đây là trường hợp hành trình sáng tạo tiểu thuyết cuả chính tôi, xin đưa làm thí dụ cho cái gọi là “metafiction” mà một số người Việt Nam dịch là “siêu tiểu thuyết.” Tôi không đồng ý với dịch thuật này, vì chính tôi viết metafiction, mà tiểu thuyết cuả tôi rất thực tế, dựa trên thực tế và chi tiết lịch sử hay chính kinh nghiệm sống của tôi, có thể bị chê là khó hiểu, nhưng không có gì “siêu” trong đó cả.

1) Năm 2020, tôi viết một truyện ngắn bằng tiếng Việt để tặng gia đình tôi (có thể là truyện cuối cùng viết thẳng bằng ngôn ngữ mẹ vì vấn đề thì giờ không có). Truyện mang tên Cánh Én Nhà Tôi, có thể được cho là một loại metafiction, vì truyện kể lại chu trình viết tiểu thuyết cuả nhân vật. Nhân vật ấy kể lại truyện mơ ngủ, hoang tưởng, không phải là sự thật trong thế giới của nhân vật ấy, chỉ là một giấc chiêm bao có tác dụng biểu tượng cho truyện kể (truyện lồng trong truyện). Nhưng giấc chiêm bao ấy là sự thật cho độc giả, và nhân vật đang viết lại giấc mơ cuả mình chính là tiểu thuyết gia, người viết tiểu thuyết cho tương lai.

Ở cuối tiểu thuyết, tác giả cho biết tiểu thuyết gia trong tương lai là ai, Cánh Én của ngày mai, chính là người đã nằm mộng, nhưng đó không phải là tự truyện, vì tiếng nói trong truyện chỉ là của tiếng nói của nhân vật mà thôi, chứ không phải của Tôi, tác giả truyện ngắn (tôi phải đứng ở ngoài truyện ngắn thì mới tạo dựng ra truyện ngắn được, vì truyện ngắn không phải là hồi ký, memoir, cuả tôi. Tôi tạo nên hồi ký hay nhật ký cuả nhân vật, chứ không phải hồi ký hay nhật ký cuả tôi).

Cuối cùng thì chính nhân vật kể lại tất cả những gì đã xẩy ra cho nhân vật ấy, và nhiều “truyện” khác, hơn thế nữa. Đó là cốt truyện mà Tôi, tác giả thật sự ngoài đời, đã tạo dựng nên về nhân vật, cho độc giả đọc. Các “truyện” đó, có thể lấy từ đời sống, hay chính kinh nghiệm sống cuả tôi, nhưng khi tôi, tác giả, nói rằng đây là dạng tiểu thuyết, thì độc giả không thể gọi tôi là nhân vật được.

Tuy nhiên, vì tôi cho nhân vật ấy đi ra khỏi thế giới của truyện nhân vật đang kể, gần như ra ngoài sự kiểm soát cuả tác giả, cho nên có những đoạn lập đi lập lại mô tả thực thể bên ngoài, đối chiếu với những gì xảy ra trong khối óc hoài niệm của nhân vật ấy. Nhân vật đã chụp ảnh chính tư tưởng hoài niệm cuả mình cho độc giả xem, ảnh thế nào thì độc giả sẽ thấy y hệt như thế, cho nên tác giả không cần thiết đứng ở bên ngoài tiểu thuyết để “edit” khối óc hoài niệm của nhân vật cho truyện ngắn được gọn ghẽ hơn. Việc mô tả lập đi lập lại tình trạng trí não và hồi tưởng cuả nhân vật chính là chủ ý cuả tác giả truyện ngắn, cho độc giả thấy nhân vật bị ám ảnh như thế nào. Và ở kết cục truyện ngắn, độc giả có thể không biết nhân vật có phải là tác giả hay không. Đó là quyền suy luận cuả độc giả.

2) Chiếc Phong Cầm Của Bố Tôi, truyện ngắn tôi viết thập niên 1990, cũng có thể là bút pháp của metafiction vì nhân vật nói chuyện với độc giả, như tác giả đang nói, kể lại những kỷ niệm về cuộc đời của cha mình.

3) Bưu Thiếp Của Nam, tiểu thuyết ngắn (novella) tôi viết thập niên 2000: Sau khi nhân vật kể xong cốt truyện – tức là truyện xẩy ra trong đời sống cuả nhân vật, thì nhân vật tuyên bố sự thật ấy mai sau sẽ trở thành “tiểu thuyết.” Như vậy nhân vật sẽ trở thành tiểu thuyết gia. Vì nhân vật xưng tôi, độc giả có thể nghĩ nhân vật chính là tác giả cuốn tiểu thuyểt độc giả đang cầm trong tay. Đó cũng có thể là một hình thức bút pháp của metafiction.

Nói tóm lại, đâu là tác giả, đâu là nhân vật, có một sự lẫn lộn, mơ hồ, gần như cố tình, qua hình thức truyện, nhưng vẫn không phải là tự truyện hay hồi ký, vì không thấy chi tiết về tác giả hiện ra trong nhân vật. Thí dụ, trong “Cánh Én Nhà Tôi,” tên nhân vật – người kể truyện — là gi? Bao nhiêu tuổi? Làm nghề gì? Cư ngụ ở đâu? Không thấy hiện ra để trở thành tác giả (Tôi). Và rất có thể nhân vật kể truyện – narrator – trong Cánh Én Nhà Tôi đã khoác lên lớp áo nhân cách hoàn toàn khác hẳn tác giả.

Tôi không cố tình viết metafiction, nhưng tự nhiên trong chu trình sáng tạo, tôi viết ra nhu vậy, và tiềm thức đi theo khuynh hướng đó mà thôi.

Sau đó, tôi đã phải tự làm người nhận xét phê bình để phân tích và đưa thí dụ từ ngay tác phẩm tiểu thuyết cuả mình, khi nói về metafiction, như qúy vị đã thấy ở đây.

TIỂU THUYẾT HIỆN ĐẠI CUẢ TÂY PHƯƠNG

Có ba tác phẩm lớn, truyện dài (novel) nổi tiếng khắp thế giới, được công nhận là metafiction, không bàn cãi. Ở phương Tây, thế kỷ 20, có Pale Fire của Vladimir Nabokov, và The French Lieutenant’s Woman của John Fowles. Tôi đồng ý.

Gần đây hơn, có tác phẩm kinh dị, House of Leaves, cuả nhà văn trẻ tuổi người Mỹ Mark Z. Danielewski. Tiểu thuyết này là truyện lồng trong truyện, được xem là metafiction vì đem luôn người ngoải đời có thật vào truyện giả tưởng, lồng trong truyện giả tưởng, mà lại cho độc giả có ảo giác cuả một sự thật nào đó.

Như tôi đã nói trên đây, Cánh Én Nhà Tôi do tôi viết năm 2020, cũng là một hình thức truyện lồng trong truyện. Tôi cho đó là một hình thức metafiction.

Thế nhưng có một thể dạng gây bàn cãi: đó là cuốn “tiểu thuyết phi hư cấu” cuả nhà văn Mỹ Truman Capote, thế kỷ 20. Ông Capote gọi một tác phẩm cuả mình, In Cold Blood, là “non-fiction novel,” có thể dịch là “chuyện thật tiểu thuyết hoá,” vì ông ta đem một câu chuyện về kẻ sát nhân, một vụ giết người mà chính ông ta đi điều tra, phỏng vấn, rồi ông ta viết ra, như thể viết một tiểu thuyết, novel. Ông ta gọi đó là “tiểu thuyết.”

Tiểu thuyết trong căn bản là hư cấu, thì làm gì có thể dạng “phi hư cấu”? Tác giả có thể hiện ra để nhắc nhở độc giả rằng họ đang đọc hư cấu, để phá vỡ chu trình đắm mình vào thế giới cuả tiểu thuyết tưởng như là chuyện thật (“suspended disbelief”). Tác giả bước vào tiểu thuyết trong sự biến dạng nguyên tắc tiểu thuyết mà thôi, dưới hình thức “post-modern metafiction.” Nhưng nếu là tiểu thuyết thì bắt buộc phải hư cấu.

Vì thế, khi Capote gọi “In Cold Blood” là “tiểu thuyết,” thì bắt buộc trong truyện kể, cho dù dựa trên chuyện thật, thế nào cũng có sự bịa đặt, nói thêm lên, nói bớt đi, cuả chính Capote. Và độc giả không thể tin Capote nói sự thật được.

Sự thật được tiểu thuyết hoá là để bảo vệ đời tư cuả người trong cuộc, và cho tác giả được quyền thêm bớt để bảo vệ các nhân vật có thật, hay bảo vệ chính sự liên quan cuả tác giả. Hoặc tác giả đưa thêm “hư cấu,” fiction, vào sự thật để mê hoặc độc giả, hoặc để dùng các chiêu thức cuả một tiểu thuyết gia, viết sáng tạo chứ không kể theo dạng hồi ký hay phóng sự trung thành với sự thật.

Trong văn chương hiện đại cuả Việt Nam, tình trạng này cũng đã xẩy ra, với truyện ngắn phóng sự Tôi Kéo Xe cuả Tam Lang. Và từ đó, người Việt Nam “đẻ ra” danh từ “tiểu thuyết phi hư cấu.” Danh từ này cũng mâu thuẫn như Capote mô tả cuốn In Cold Blood cuả ông ta viết.

Vì thế, theo tôi, In Cold Blood và Tôi Kéo Xe không phải là metafiction. Mà là chuyện thật, được tiểu thuyết hoá. Hai tác phẩm là kết quả cuả sự trộn lẫn báo chí/phóng sự với nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết.

Tác giả phải đi vào tiểu thuyết như một phần cuả bủt pháp thì mới là metafiction.

TIỂU THUYẾT KINH ĐIỂN CỦA THẾ GIỚI

Metafiction là một bút pháp được công nhận trong thời kỳ “hậu hiện đại” (post-modernism), thế kỷ hai mươi, của lịch sử văn chương, con người. Nhưng thực ra metafiction đã ra đời trước đó nưã. Ngay cả những tác phẩm kinh điển thời xưa như Don Quixote và Canterbury Tales cũng được các nhà văn học sử cho là thể dạng metafiction.

Nếu nhìn metafiction kiểu như tôi trình bày, thì theo tôi Hồng Lâu Mộng của Trung Hoa ngày xưa cũng là một hình thức metafiction. Vì là truyện lồng trong truyện.

Ngàn Lẻ Một Đêm cũng là metafiction vì là câu truyện kể những câu truyện.

TIỂU THUYẾT CUẢ VĂN HỌC VIỆT NAM NGÀY NAY, HẢI NGOẠI

Theo bà Trịnh Thanh Thuỷ thì có Sông Côn Mùa Lũ, tiểu thuyết lịch sử của Nguyễn Mộng Giác là thể loại metafiction. Nhưng bà ấy lại định nghĩa metafiction khác tôi. Vì thế, tôi sẽ phải đọc Sông Côn Mùa Lũ thì mới có thể giải thích hay kết luận được đó có là metafiction hay không, ở phương diện nào. Quý vị nào đã đọc, có ý kiến, thi xin cho tôi biết.

MỘT ĐỊNH NGHĨA CÓ THỂ CHẤP NHẬN

Nói tóm lại, metafiction có thể dịch là tiểu thuyết về tiểu thuyết, tiểu thuyết của hậu hiện đại, tiểu thuyết theo sau tiểu thuyết hiện đại, tiểu thuyết trong tiểu thuyết, hư cấu trong hư cấu, hiện thực trong hư cấu, hư cấu trong hiện thực. Nhưng căn bản cuả metafiction vẫn là hư cấu. Ở dạng metafiction, tác giả có thể đi ra, đi vào tiểu thuyết khơi khơi, làm cho ranh giới của hư cấu, của lịch sử bị lung lay hay mờ ảo. Chữ “siêu” không nói lên được thực trạng chuyển biến này. Trong metafiction, ranh giới giữa sự thật cuộc đời và hư cấu có thể trở thành mờ ảo, nhưng nếu tảc giả nói tác phẩm là fiction, thì độc giả cần phải tôn trọng ranh giới cuả tiểu thuyết, không thể nói nhân vật là tác giả được.

Thêm nữa, dùng chữ ”tiểu thuyết hư cấu” theo tôi là sai, thưà thãi, vì tiểu thuyết (novel) chính nó là hư cấu rồi. Và như thế, thì cụm từ

“tiểu thuyết phi hư cấu” cũng sai ờ khía cạnh “semantics/etymology” – ý nghĩa và lịch sử cuà ngôn ngữ.

Sở dĩ novel, nghệ thuật hư cấu, được gọi là “tiểu thuyết” trong kho tàng ngôn ngữ Hán Việt, đó là vì nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết từ trong căn bản phải dựa trên mệnh đề, hoài bão của tác giả, cùng một tính chất với văn chương nghị luận. Nhưng vì tiểu thuyết chọn hình dạng hư cấu của nghệ thuật tưởng tượng, cho nên bị hạ giá thành một “mệnh đề nhỏ/ thuyết minh nhỏ) (nghĩa đen của từ “tiểu thuyết”), trong khi văn chương nghị luận, điều trần, phân tích lịch sử, etc, là những “thuyết minh lớn” của khối óc con người. Gọi thế giới cuả sáng tạo là “thuyết minh nhỏ” chỉ là hình thức nói khiêm nhường rằng thuyết minh theo hình thức sáng tạo chỉ là để “giải trí” mà thôi. “Mua vui cũng được một vài trống canh.” (Nguyễn Du)

Trong chiều hướng đó, như đã nói ở trên, thì “tiểu thuyết phi hư cấu” cũng là một danh từ mất căn bản ngôn ngữ. Danh từ đúng nghĩa phải là “creative non-fiction” hay “literary non-fiction,” nên dịch là “tác phẩm văn chương phi tiểu thuyết.”

NHÌN LẠI BỐI CẢNH LỊCH SỬ TIỂU THUYẾT CUẢ VIỆT NAM

Nghệ thuật “tiểu thuyết” đến với VN trong thòi kỳ Pháp thuộc là một “nhập khẩu” cuả Tây Phương. (Nếu như tôi dùng chữ cuả miền Nam trước bảy-lăm, thì tôi phải gọi nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết là “hàng nhập cảng.) Nhưng thật ra, các hình thể cuả “tiểu thuyết” đã có mặt trong cổ văn VN từ xưa, với “Bần Nữ Thán” cuả tác giả vô danh, ngay trong văn học dân gian như Phạm Công Cúc Hoa, qua đến Bích Câu Kỳ Ngộ, sau nưã là “Lục Vân Tiên” của cụ Nguyễn Đình Chiểu (1822-1888), chỉ nêu vài thí dụ. Truyện Kiều cuả Nguyễn Du (1766-1820) là một trường thiên tiểu thuyết dù rằng cốt truyện là cuả Thanh Tâm Tài Nhân. Tất cả “tiểu thuyết” cổ văn Việt Nam đều theo thể thơ, hoặc theo thể sân khấu “nhạc kịch” cuả người bình dân như các “tuồng” chèo cổ cuả các tác giả khuyết danh.

Trước khi chấm dứt tiểu thuyết, Nguyễn Đình Chiểu và Nguyễn Du đều xuất hiện trước độc giả để kết luận về triết lý và đạo đức bản thân, cho nên truyện cổ Việt Nam hầu hết mang bản chất cuả metafiction, phần nào.

Qua dạng “kim văn” để đối chiếu với “cổ văn,” thời Pháp thuộc đem đến cho Việt Nam những Hồ Biểu Chánh, Lê Văn Trương, Vũ Trọng Phụng, Nam Cao, Tam Lang, v.v., và sau nữa là sự thành hình và đóng góp của Tự Lực Văn Đoàn với truyện ngắn và truyện dài mà hình thức kể truyện và xây dựng nhân vật qua chữ Quốc Ngữ mang ảnh hưởng Tây Phương, không nhiều thì ít. Sau hiệp định Geneve, tôi xin tạm gọi sáng tác tiểu thuyết cuả miền Nam (VNCH) là không khí của tự do tư tưởng và tự do sáng tạo (trong ý nghĩa đối chiếu với “Nhân Văn Giai Phẩm” cuả miền Bắc, hay “Trăm Hoa Đua Nở/Cách Mạng Văn Hoá” cuả Mao Trạch Đông, hoặc điển hình sự đàn áp giới văn nghệ và trí thức, như với tác giả Boris Pasternak ở Soviet (người viết cuốn Dr. Jivago được giải Nobel thế giới trong gian đoạn Chiến Tranh Lạnh cuà quốc tế).

Hình thức metafiction có xuất hiện trong các tác phẩm này? Tôi không có câu trả lời, vì không thể đọc hết với câu hỏi này trong đầu. Hơn nữa, sự phân loại ấy có ích lợi gì cho chúng ta ngày hôm nay?

Còn miền Bắc và Việt Nam CHXHCH ngày nay thì sao? Có thấp thoáng metafiction?

Tôi chỉ xin đưa một vài nhận xét sau đây.

NHU CẦU CHO TÁC GIẢ TẠO RANH GIỚI, RỒI LẠI PHÁ RANH GIỚI GIỮA THỰC VÀ ẢO TRONG KHUNG TRỜI TIỂU THUYẾT, BỐI CẢNH LỊCH SỬ VIỆT NAM

Trong tập tiểu luận “Gender Equality and Women’s Issues in Vietnam – The Vietamese Woman: Warrior and Poet,” ấn bản bởi Đại Học Washington năm 1999, tôi dùng “bộ ba” tác phẩm sáng tạo cổ văn Việt Nam – Cung Oán, Chinh Phụ, và Kiều (tạm gọi là “Oán-Chinh-Kiều“), để mô tả hiện tượng và chủ ý sáng tác cuả trí thức Việt Nam trong giai đoạn tao loạn và chia cách nhất cuả Việt Nam, kéo dài hậu quả của thời Hậu Lê, Lê Mạc (Nam-Bắc Triều), Lê-Trung-Hưng/Lê-Mạt/Lê-Sơ, Trịnh Nguyễn phân tranh, và sau đó là Tây Sơn-Nguyễn, cho đến sự hình thành cuả Nguyễn Triều năm 1802, Gia Long lên ngôi, thống nhất sơn hà và chính thức triều cống nhả Thanh, đặt kinh đô ờ Huế (việc dời kinh đô xoá đi ảnh hưởng thời vàng son của Lê Triều và sự xa hoa quyền quý của chúa Trịnh ở Thăng Long, nhằm củng cố công nghiệp Nam tiến của chín chúa Nguyễn qua việc tập trung quyền lực vào kinh thành ở Phú Xuân). Thời hoàng kim Golden Age cuả Lê Thánh Tôn là tâm trạng hoài cổ tìm thấy trong thất ngôn bát cú Bà Huyện Thanh Quan.

Đây là bức tranh mấy trăm năm lịch sử nhiễu nhương tranh quyền cố vị cuả VN, mỗi biến cố lịch sử có thể ảnh hưởng đến năm thế hệ, theo khảo cứu ngày nay về “aftermath of war.” Đây là giai đoạn triều thần cướp ngôi vua, nền quân chủ cuả nhà Lê bị thử thách, huynh đệ tương tàn, trí thức giết hại nhau, võ quan tranh quyền cố vị, một vua hai chúa, đất nước chia đôi trong vấn đề quyền lực, nội chiến, giai cấp văn võ phải chọn lựa theo ai, nhân tài cũng như tài nguyên và chủ quyền quốc gia bị tiêu hao, phân tán mấy trăm năm, sau cùng thì quý tộc nhà Nguyễn phải đi cầu viện Xiêm La và các cố đạo Pháp.

Nói về Oán-Chinh-Kiều — tiêu biểu cho sáng tạo văn chương Việt Nam thời buổi lịch sử kéo dài rất nhiễu nhương ấy — thì chỉ có Kiều là đúng nghĩa tiểu thuyết, với cốt truyện lâm ly, có “climax,” cao điểm, và có “denouement,” sự giải toả của cao điểm (gọi nôm na là “có hậu”), nhưng đó là nội dung vay mượn, mà có thể tác giả Nguyễn Du cố tình để tránh một tác phẩm sáng tạo mà cốt truyện đặt tại VN. Còn Cung Oán và Chinh Phụ chỉ là những trường thi mà thôi, nhưng có sự xây dựng cảnh trí, nhân vật, và sự mô tả tâm trạng nhân vật tiêu biểu cho tiểu thuyết.

Các tác giả Nguyễn Gia Thiều, Đặng Trần Côn/Đoàn Thị Điểm/Phan Huy Ích, và Nguyễn Du, có thể không sống qua tất cà các triều đại hay biến cố lịch sử kể trên, nhưng ảnh hưởng trên tư tưởng và thái độ sống cuà nghệ sĩ sáng tạo luôn luôn là ảnh hưởng trường kỳ, trước và sau thời gian sống, có nhiều khi vô thức – những gì đã kết cấu trước khi họ sinh ra đời, và sẽ xầy ra sau khi họ đã nhắm mắt, vì tâm tư sáng tạo thường được nghệ sĩ trí thức đặt vào tâm trạng “legacy,” gọi là “sau khi đã chết, còn lại cái gì?” – một sự sửa soạn cho ngày nằm xuống.

–Nguyễn Gia Thiều (1741-1798) là con cháu cuả quý tộc Chuá Trịnh, nhìn thấy cảnh vua-chúa tiếm quyền, và chuyện thâm cung bí sử;

–Đặng Trần Côn (1705-1745) là sĩ phu thời Lê Trung Hưng, cũng kém may mắn về thi cử để tiến thân;

–Đoàn Thị Điểm (1702-1748) sống cùng thời với DTC, đã từng phải từ chối việc tiến cung dâng bà cho Chuá Trịnh, và về sau bà dạy học trong cung rồi từ chức, và chịu cảnh chia tay với chồng ít nhất là ba năm, lúc tuổi đã lớn, vì tiến sĩ Nguyễn Kiều nhận việc đi sứ sang Tàu; khi chồng về thì bà chết sớm.

–Trước thời Đặng Trần Côn – Đoàn Thị Điểm, đã có cuộc chiến tranh Lê-Mạc kéo dài trên 50 năm và chủ quyền quốc gia phân tán vì nhà Mạc chiếm ngôi. Cả nhà Mạc và nhà Lê đều triều cống nhà Minh.

–Phan Huy Ích (1751-1822), có thể là dịch giả Chinh Phụ Ngâm (một nghi vấn văn học sử), là đại thần cuả thời Lê Trung Hưng, Tây Sơn, và Nguyễn.

–Phan Huy Ích và Nguyễn Du (1766-1820) sống qua bốn giai đọan: Lê-Trịnh-Tây Sơn-Nguyễn.

Trong tiểu luận, tôi gọi bộ ba Oán-Chinh-Kiều là hiện trạng sáng tác “Cái Chai Trong Vắt.” Đặc điểm cuả “bộ ba” này là dùng nhân vật phụ nữ – tiêu biểu cho người dân yếu đuối, bị trị, và sự bất lực cuả trí thức trước hoàn cảnh quốc gia, phải chứng kiến những tai ương cuả dân đen không quyền lực, cùng với nỗi buồn bất lực cuả chính mình. Nam nhân trí thức đồng hoá tâm trạng cuả mình với sự bất hạnh của nữ nhân kém may mắn, không thoát được sự kìm kẹp cuả thời đại, xã hội và định mệnh (trong thế kỷ hai mươi, đây là một hiện tượng văn học, văn hoá, xã hội cuả cả thế giới trong khung cảnh của phong trào thực dân, thường xẩy ra ờ các nước chậm tiến, bị cai trị bởi các đế quốc – the colonized males identified with the plights of the colonized females. Tôi tạm gọi là “sự chuyển đạt cá thể,” transferred identity).

Trong “tâm thức chuyển đạt cá thể” ấy, việc xây dựng nhân vật và bối cảnh tiểu thuyết trở thành cái chai trong vắt, chuyên chở hoài bão hay sự than thở cuả nhà thơ/nhà văn, trong đó, miếng thuỷ tinh trong vắt tạo nên cái chai trở thành vô hình, một bức tường mà ở ngoài trông thì không ai nhìn thấy. Và các chủ thể nào trong số độc giả đã chuyển đạt cá thể cuả mình vào nhân vật sống trong chai thì sẽ thấm thía mục đích và tư tưởng cuả tác giả, người tạo nên cái chai, vì họ biết rằng tác giả đã để nhân vật vào cái chai trong vắt, chứ thật ra nhân vật chính là họ ở phía ngoài, hay là chính tác giả đứng phía ngoài cái chai.

Và vì thế, ở khía cạnh vô thức, độc giả có thể không còn phân biệt đâu là thật đâu là ảo. Những gì bên trong cái chai và những gì bên ngoài cái chai trờ thành một, không phân biệt, vì nếu có bức tường, thì người đọc không nhận ra bức tường do cái chai trong vắt tạo nên. Độc giả vì thế nhận được tâm tình cuả tác giả qua nhân vật. Thế nhưng, tiểu thuyết gia vẫn có thể trốn tránh trách nhiệm hay sự chú ý cuả bạo quyền nhờ cái chai trong vắt ấy. Cái chai chính là sự che chở cho tác giả qua thể dạng cuả tiểu thuyết.

Khi nhìn vào công thức “vô hình” mà tôi gọi là ‘Cái Chai Trong Vắt” của văn chương sáng tạo “Oán-Chinh-Kiều,” chúng ta nên đặt những câu hỏi:

–Tâm sự Nguyễn Gia Thiều có hiện ra trong Cung Oán, thay thế cho tiếng than của cung nữ? Có câu nào là cuả Nguyễn Gia Thiều nói thẳng với độc giả không, qua cái chai trong vắt của ông tạo ra? (Đây là Cung Nữ ở bên Tàu, chứ không phải là thâm cung bí sử cuả chúa Trịnh; đó là cái chai “tiểu thuyết” mang chỗ ẩn náu đến cho Nguyễn Gia Thiều).

–Tâm sự của Đặng Trần Côn/Đoàn Thị Điểm có hiện ra trong Chinh Phụ không? Tấm kiếng giữa ảo và thực thì vô hình, có thể người đọc vẫn nghe tiếng than cuả Đoàn Thị Điểm, cái uất ức cuả Đoàn Thị Điểm, nhưng “cái chai” trong Chinh Phụ để bảo vệ tác giả thì khá rõ ràng. Thí dụ: khi mô tả sứ mệnh của chinh phu, trong bản chữ Hán, Đặng Trần Côn nói đến… Mã Viện; Đoàn Thị Điểm và Phan Huy Ích sửa lại thành “Phục Ba” cho đỡ… kỳ, vì ai mà không biết Mã Viện đã diệt Hai Bà Trưng lập quốc. Đây là chuyện giặc giã chiến tranh ở nước Tàu, đâu phải ở Việt Nam! Người chinh phu nào của Việt Nam mà lại đi theo chiến lược của… Mã Viện khi đến “Man Khê ? (“Săn Lâu Lan rằng theo Giới Tử, Đến Man Khê bàn sự Phục Ba.”)

–Truyện Kiều xẩy ra ở bên Tàu, “rằng năm Gia Tĩnh triều Minh...” Trong bản chính tiểu thuyết, Thanh Tâm Tài Nhân không hề nhắc đến sự thanh bình yên ồn cuả Bắc và Nam Kinh; vậy mà Nguyễn Du thêm vào, “Bốn phương phẳng lặng, hai kinh vững vàng...” Như thế, rõ ràng Nguyễn Du không nói chuyện chiến tranh Đằng Trong Đằng Ngoài của Việt Nam, than thở cái bất công của thời đại Lê Trung Hưng hay Nguyễn Triều, mà ông chỉ nói truyện tưởng tượng bên Tàu; đó là “cái chai” cho Nguyễn Du trốn tránh. Thế nhưng, độc giả thì thấy cái gì? Độc giả đọc Kiều cứ như là chuyện thật cuả người Việt Nam (suspended disbelief). Người bình dân say mê Kiều, lẩy Kiều vang vọng từ Bắc vô Nam chẳng ai nhớ cô Kiều là người Tàu. Có thể nào không ai thấy cái chai chuyên chở Truyện Kiều để tạo nên tiểu thuyết? Cô gái nhỏ 16 tuổi nào, nàng Kiều tu tại gia nào 35 tuổi mà “cầm kỳ thi họa” uống rượu đánh cờ với Kim Trọng như là bạn đồng song vậy? Hình như “cầm kỳ thi họa” chén tạc chén thù chỉ là đặc tính cuả văn nhân trí thức Việt Nam như Nguyễn Du thì phải. Đâu là cái chai? Đâu là tấm kiếng trong vắt? Ai thấy cái gì trong Truyện Kiều?

Nguyễn Du có thể qua đời với trái tim trĩu nặng, nhưng không bị tru di tam tộc, mà Nguyễn Trãi và Cao Bá Quát thì chịu chết thảm thương, và tác phẩm bị tiêu diệt.

Trong lòng văn hóa và văn học Việt, phi chính trị, cả ba đều trở thành bất tử. Nhưng kết quả đó chỉ có trong trường hợp của Nguyễn Trãi và Cao Bá Quát vì có sự bạch hoá cuả lịch sử sau cái chết, và có sự nuôi dưỡng hai thi nhân này cuả lịch sử dân tộc chính thống.

Nguyễn Trãi và Cao Bá Quát hành động, thay vì viết tiểu thuyết như Nguyễn Du để có sự bảo vệ cuả “Cái Chai Trong Vắt” nhắm vào trái tim con người — tiếng nói cuả tiểu thuyết.

“Cái Chai Trong Vắt” ấy cũng vẫn có thể bị tiêu diệt và xóa đi, nếu không có sự tồn tại cuả lịch sử và văn học sử.

THAY LỜI KẾT

Trong tận cùng cuả lý thuyết và nghệ thuật tiểu thuyết, thí dụ lớn nhất và rõ nhất cuả metafiction chính là “The Tempest” cuả Shakespeare, metatheatre, vở cuối cùng của sự nghiệp Shakespeare trước khi kịch tác gia qua đời, trong đó, màn cuối cùng cho thấy nhân vật chính, một phù thuỷ và cũng là một nhà vua đã bị thoán ngôi, đến gần khán giả và xin khán giả thả cho nhân vật ấy được bước ra khỏi vở kịch để giã từ sân khấu.

WND copyrighted 2020, 2021

french education in Vietnam the work of Dr. Duong Duc Nhu

https://usvietnam.uoregon.edu/en/11111-2222-1/

https://usvietnam.uoregon.edu/en/11111-2222-1/

SOCIETY & CULTURE

Objectives and Methodology for the Study and Research of Education in Vietnam during French Occupation: A Five-Dimension Approach

Published 2 months ago

on January 9, 2022

By © Dương Đức Nhự (Posthumous), London School of African and Asian Studies; Ph.D. Educational Leadership, Southern Illinois University.

with an introduction, editing, and commentaries by W.N. Duong Nhu-Nguyen

I. INTRODUCTION: The need to look at the past, and how?

The 21st century has seen what seems to be a reemergence or rejuvenation of scholarly research work on education in Vietnam during the 20th Century’s French colonization. Such a collective body of work typically came from Vietnam and often dealt with the topic descriptively for historical purposes. Perhaps the impetus is a response to Vietnam’s modernization, a coming-of-age tour-de-force: Because the post-Doi Moi era has brought about the creation of civil societies to advocate for social changes, there is a need, whether conscious or subconscious, for Vietnamese scholars to re-examine root causes and the past colonial setting that precipitated what today’s Vietnamese leadership has always proclaimed proudly as the “Vietnamese revolution” of 1946-1975. Communist leaders might incline to describe colonial education as brutally oppressive in order to fortify the need for an ideological revolution brought about by the proletariat whom the French kept out of the educated class. Of late, many scholars, authors, and historians have raised the issue of whether the Vietnamese “revolution” that brought about decolonization was a “communist revolution,” or whether it was a national revolution, a result of Vietnamese patriotism, on behalf of all Vietnamese including the French-educated.

At the end of the Vietnamese War (and, hence, the inception of a Vietnamese American diaspora), in 1975, Dr. Duong Duc Nhu, formerly University of Saigon’s associate professor of English and Applied Linguistics and a former Fulbright Scholar sent by the Republic of Vietnam to Southern Illinois University, opined that French education in Vietnam should be observed and studied in five identified dimensions. In his view, a single, one-path research focus is not adequate to help readers understand and analyze the forces that governed and drove Vietnamese learners during the French occupation. Accordingly, he performed this five-dimensional study and documented it in his 542-page monograph of limited distribution, written in English, supported with footnotes, endnotes, and a bibliography, currently on microfilm at Southern Illinois University, titled Education in Vietnam under French Domination 1862-1945 (pub. 1978). This article describes such a multidimensional approach and presents its justification and results.

II. PREMISE: A prolonged national crisis and chaos such as the French occupation of monarchic and agricultural Vietnam during the 20th Century deserve multi-dimensional empirical scrutiny free from propaganda or geo-political bias.

The five-dimensional approach is necessary because the complexity of the colonial era and its stressful impact upon Vietnam’s learning public dismantled the country’s age-old learning culture, challenged the ethics of its traditional educational structure, and subjected Vietnamese students to pro-longed chaos: Never before were generations of Vietnamese scholars and students made to face and absorb three different linguistic and cultural systems almost contemporaneously:

1) the traditional Chinese-based Han Tu and its Vietnamese derivative chu Nom. (For centuries, the development of chu Nom evidenced Vietnam’s independent and creative spirit against Chinese characters as the principle means of learning and upward mobility; although Chu Nom became very popular among the Vietnamese public, and was frequently used in native literature, Chu Nom was never formally adopted as the official written language of ancient Vietnam, especially in national examinations);

2) the modern chu quoc ngu, using the Roman alphabet and representing the fresh “wind” of the 20th century, accompanied by Catholicism as an addition to Vietnam’s harmonized religious life (20th-Century Vietnam’s religious life consisted of Catholicism, Buddhism, and Taoism, which were cemented together into philosophical coherency by the people’s uniform adherence to the culture’s practice of ancestor worship, regardless of social class or religion); and

3) the newly arrived European model of Latin and French, which, as aided by Catholic schooling for converted Vietnamese, also represented the exotic and the powerful – that advanced by the colonist government especially in CochinChina (Nam ky).

During French occupation, the sufferings of the educated class — holding on to its roots and traditions while struggling to adopt newer ways — were amply evidenced by the works and lives of scholars, creative writers and poets: to name a few:

(1) “tiến sỹ” (Confucian “Ph.D.” holder) and poet Nguyen Khuyen;

(2) traditionally schooled Tu Tai Tran Te Xuong, a poet-satirist;

(3) well-admired resistant-cum-conformist poet Tan Da Nguyen Khac Hieu;

(4) Cu Nhan Huan Dao Vu Khac Tiep (the most recent, and perhaps the last, yet ironically higher-ranked, successor to Cao Ba Quat’s public-teaching post in Son Tay; Cao Ba Quat (1809-1855) was a progressive disillusioned mandarin nationally admired for being a language prodigy in his youth, and for his prolific and sophisticated poetry mostly written in Chinese. He led an unsuccessful revolt against the Nguyen Dynasty as a strategist for montagnard rebels, during his tenure as the official teacher for Quoc Oai District, in the province of Son Tay, west of Hanoi). The mandarin-poet died with his cause; his extended family were also executed for treason by the Nguyen royal court);

(5) the nostalgic Vu Dinh Lien (author of the famous, poignant mid-20th-century poem about “the old teacher of Chinese characters selling his calligraphy on the street” – these verses were learned by heart by generations of Vietnamese (Ong Do Gia “…bay muc tau giay do, ben pho dong nguoi qua…”).

III. DESCRIPTION OF THE FIVE DIMENSIONS: Horizontal, Chronological, Territorial, Vertically Structural, and Content-Based

A thorough study of France’s educational system implemented in occupied Vietnam (consisting of Tonkin and Annam, the two protectorate states, and colonized French Cochinchina) should be conducted and presented from five different angles. Each dimension should have its own objectives of the investigation. The result should lead to empirical data and verification that support the following five observations:

1. FIRST DIMENSION — the horizontal dimension:

This first dimension reveals three patterns of education that coexisted in Vietnam under French occupation, for the most part. In other words, for 83 years (1862-1945), the French implemented three different types of education: Confucian Education; French Education; and Franco-Vietnamese Education. After 1919, the first type, the Confucian model, was extinguished, but its remnant remained in the populace, while the other two types continued to co-exist.

In the first pattern, pre-colonial Vietnam’s free and secular education continued from 1862 to 1919, based on Confucianism, with Chinese characters as the official medium of instruction (i.e., traditional “Confucian Education,” Nho hoc). This pattern of education existed in Vietnam long before the French arrived, from the 10th century to the end of the second decade of the 20th century. This first pattern neglected physical exercises and stressed ethics built on the Confucian “gentleman’s” mode of behaviors (for example, the five virtues: compassion, gratitude, manners, wisdom, and credibility). The French abolished this pattern of Confucian Education in 1919.

Specifically, the Confucian Education pattern did not survive long in Cochinchina after 1867, when the French occupied the remaining Western provinces of Southern Vietnam (ba tinh mien Đong Nam Ky) by force and then by treaty. In Tonkin, Confucian Education officially survived until 1915, and, in Annam, until 1919.

In the second pattern, authentic French education was transplanted into Vietnam, reserved primarily for French children who lived in Vietnam. This pattern of French Education enjoyed high social prestige and the best support from French administrators.

This imported pattern of education was termed “French,” or “metropolitan” in Indochina, modeled after the educational system available in nineteenth-century France. It was basically reserved for the French, and naturalized French children living in Vietnam, as well as for a very limited number of Vietnamese children enjoying such educational privilege, or children of other nationalities living in Vietnam. Substantively, this pattern of education had relatively higher quality and not just social prestige, compared to the traditional Confucian pattern, or the Franco-Vietnamese pattern (described below).

In the third pattern, the French designed a Franco-cum-indigenous concept, or Franco-Vietnamese Education, using Vietnamese as the medium of instruction from primary to higher education. This pattern was instituted for the whole of Indochina in 1918, tailored to the practical conditions of the local environments in order to further French interest (although it later bore certain aspects of a French “mission civilisatrice” bestowed upon the indigenous population, as per the more liberal policy and agenda of Governor-General Albert Sarraut (1911-1913).

This third pattern was basically modelled after the French pattern in terms of organization and curriculum, with some adaptation to the practical conditions of local environments. This pattern covered two different periods, depending on the territory(ies) involved:

In Cochinchina, Franco-Vietnamese Education was installed right away in 1862, when the French successfully took over the three Eastern provinces of Southern Vietnam (ba tinh mien Tay Nam Ky).

In Annam and Tonkin, which became French protectorates in 1884, Franco-Vietnamese Education was organized approximately more than twenty years later. Assumably, the existing traditional Confucian Education system filled such a 20-year gap, beginning in 1862, administered by the Vietnamese royal court.)

2. SECOND DIMENSION — the chronological dimension:

This second dimension should be presented as a chronology of French fundamental reforms gradually or incrementally implemented from 1862 to 1945. The objective of this chronological scrutiny should be to bring out the general direction of, and the policy behind, educational practices and development designed and implemented by France. Hence, the administrative organization of each system of reform implemented should be reported. In that sense, a descriptive approach is required, in order to support and document policy analyses.

Attempts should be made to report from the diachronic viewpoint the fundamental educational reforms carried out by the French during the period of 1862-1945. This author believes that these reforms reflected a consistent general direction and implementation of various educational policies followed by French administrators during the entirety of the French occupation. These reforms were not piecemeal reactive measures to cope with exigencies or to meet ad hoc indigenous needs.

From a synchronic viewpoint, the administrative organization of the educational system implemented under each reform should also be described, with the focus on the controlling mechanism and decision-making structure for each reformed system. In summary, the overall format of administrative organization remained relatively static since 1931 (the descriptive documentation of cumulative previous reforms was published for an exhibition at the International Colonial Fair in Paris in 1931).

3. THIRD DIMENSION -– the territorial dimension:

This third dimension is necessary because Vietnam under French occupation was divided into three territories. In order to preempt Vietnamese political uniformity as the root of protest, French rulers wanted to capitalize on Vietnam’s existing history of regionalism (fortified by hundreds of years of conflicts between Trinh and Nguyen Lords, both proclaiming to serve the Le Emperor seated in the “northern City of the Flying Dragon, land of the 1000 years of culture” (thanh Thang Long, ngan nam van vat) (today’s Hanoi). The Trinh-Nguyen conflict was followed by territorial wars between descendants of the Nguyen Lords and the Tay Son rebels).

To realize this “division-to-rule” goal, France divided Vietnam into three states: two protectoral states (North and Central) and one colony (South). Accordingly, under the territorial dimension, the presentation should include:

a) description of the French educational system applied to the colony of Cochinchina, divided into two successive periods: (i) the period ruled by the Admiral-Governors, 1862-1879, and (ii) the period ruled by the civilian Governors, 1879-1945; and

b) description of the educational system applied to the protectorate states of Annam (central Vietnam where the Emperor resided) and Tonkin (northern Vietnam, considered to be the origin of nation-building, and the center of traditional Vietnamese intellectual and creative life). Description of the two protectorate states’ educational system should be distinguished and contrasted against that found in the colony of Cochinchina (Southern Vietnam, considered to be the most agriculturally and commercially prosperous region).

More specifically, Annam and Tonkin should be studied together because they both became French protectorates in 1884, and, as a result, bore common educational characteristics because of contemporaneous implementation. In fact, the French had learned several lessons and had experienced the local environment in their educational dealings in Cochinchina before they started a system of education for the two protectorate states. Cochinchina, therefore, should be studied separately from Annam and Tonkin, not only because of the geographical, political, and administrative division designed by the French but also because, as a French colony, Cochinchina had offered French rulers the opportunities to experiment with what they wanted to do in education for native Vietnamese. Although historically, the Court of Hue was found to be involved in anti-French activities and resistance movements started in Cochinchina, these interferences were on military and political grounds, rather than as educational protests.

4. FOURTH DIMENSION – the vertically structural dimension:

This fourth dimension is based on the five successive levels of education organized by the French: elementary, primary, advanced primary, secondary, and higher education. As to higher education, for the whole of Indochina (consisting of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos), only one university existed: the Indochinese University founded in Hanoi in 1907.

The aforementioned five levels of education, including the two sublevels (primary and advanced primary), only came into existence under French occupation. The distinction among the three principal levels of education (primary, secondary, and higher education) did not clearly exist in Vietnamese traditional schooling. The three principal levels under French occupation were subdivided as follows:

Primary education in French-dominated Vietnam consisted of three successive cycles: (1) the elementary cycle (three years), (2) the primary cycle (three years), and (3) the higher-primary cycle (four years).

Secondary education consisted of two years of study before 1927 and was changed into three years thereafter.

Higher education generally required from three to seven years. The whole length of higher education depended on the institution and the specialty chosen.

5. FIFTH DIMENSION — the content-based dimension:

Last but not least, the fifth dimension is subject matter- or content-based. This dimension should include an examination of the three subject-matter types of education dispensed at various schools in Vietnam, namely General Education, Technical Education, and Physical Education. Other types of education such as adult education, mass education, special education, and the like, were not officially organized by the French administration. As part of the analysis under this “content” dimension, one must ask why these specialized or supplemental types of education were neglected or ignored, and what impact such inadequacy created on the inhabitants of French Indochina.

IV. IMPORTANT DEFINITIONS: Geographical names that carry significant historical and “educational” meanings

To lay the foundation for the scrutiny, at a minimum, five geographical terms need explanation and clarification, based on terminologies used during the Nguyen Dynasty and French occupation: (1) Vietnam, (2) Annam, (3) Tonkin, (4) Cochinchina, and (5) Indochina.

(1) Vietnam: Vietnam was a unified nation prior to the French occupation. The country got this name in the early nineteenth century when Emperor Gia Long, a descendant of the Nguyen Lords and founder of the Nguyen Dynasty, came to the throne in 1802, having successfully united the Southern and the Northern parts of the country after approximately 300 years of civil wars among three rulers: the Nguyen Lords, the Trinh Lords, and the Tay Son Brothers, all of whom allegedly supported the Le Emperors.

(2) Annam: During the French occupation, the Vietnamese were referred to by the French as Annamites, as French divided Vietnam into three separate states, Cochinchina, Annam, and Tonkin, forming the French Union of Indochina. Annam as a state of Indochina refers to Central Vietnam, including the following provinces: Thanh-hoa, Nghe-an (including Vinh), Ha-tinh, Quang-binh (including Dong-hoi, Quang-ngai, Quang-tri), Thua-thien (including Hue’), Quang-nam (including Hoian), Quang-ngai, Khanh-hoa (including Nha-trang), (Binh-dinh (including Qui-nhon), Binh-thuan (including Phan-thiet), Kontum , and Langbiang (including Da-Lat). (The names in parentheses indicate the chief-lieu towns, i.e., towns in which resided the governmental offices and the office of the province chief. Today, the government of Vietnam might have changed these names, redesignated their geographical boundaries, or reclassified their administrative organization.)

It must also be noted that in Vietnamese, the term “Annam” also means Vietnam as contextually related to French domination. So, “I am Annam” (Toi la nguoi An Nam) means “I am a native of Vietnam.” After 1945, this generic meaning became very common among Vietnamese because of its “identity” connotation as an assertion of national differentiation connected to the colonial era. Today, it’s rarely used in such a generic sense except in a literary or historical context.

(3) Tonkin: The name Tonkin referred to Northern Vietnam, and consisted of 27 provinces: Cao-ba` ng, Bac-can, Bac-ninh, Ha-dong, Ha-giang, Ha-long, Hoa-binh, Hung-yen, Kien-an, Lai-chau, Lang-son, Lao-kay, Mong-cay, Nam-dinh, Ninh-binh, Phu-lang-thuong, Phu-ly, Phu-tho, Phuc-yen, Quang-yen, Son-tay, Sonla, Thai-bi`nh, Thai-nguyen, Tuyen-quang, Vinh-yen, and Yen-bay.

(4) Cochinchina: This name was used herein to denote Southern Vietnam with six provinces under the Nguyen Dynasty: Gia-dinh, Bien-hoa, Dinh-tuong,

Vinh-long, An-giang, and Ha-tien. The first three constituted what was usually referred to as the Eastern provinces, and the rest as the Western provinces of Cochinchina.

(5) Indochina: This name was the short form for a political entity created by France and recognized internationally. Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos formally named “the Indochinese Union” (L’Union Indochinoise) French occupation, more commonly known in the West as “French Indochina” (L’Indochine Francaise). This political entity was arbitrary and artificial in order to show French domination, at least in the sense that the so-called three Vietnamese states forming Indochina were actually one unified statehood prior to French occupation, and the Vietnamese inhabiting those three parts of the former Vietnam spoke the same language: Vietnamese, sharing the same history and were subjects of the same emperor, whereas the people of Laos spoke Laotian, and the Cambodians spoke the Khmer language, each group shared separate history and were subjects of different sovereignty.

As to Vietnam, in this author’s view, the artificiality of the term “Indochinese Union” reflected the philosophy of divisiveness purposefully implemented during the French occupation, by deepening and emphasizing the differences in historical, geographical, dialectal, and cultural practices of the three regions of Vietnam. (“North” was the situs of original Vietnamese nation-building, independent from China; “Central” was primarily land donated to Dai-Viet (the predecessor name of Vietnam) by the Kingdom of Champa as “dowery” for a political marriage between a Vietnamese Tran princess and Jaya Simhavarman III, a Champa King (a Dai-Viet/Champa coalition against China); and “South” was the result of the various Lord Nguyens’ “Southern” expansion plan, including more political marriages between Nguyen princesses and Lords of other Khmer cultures in the southern part of the peninsula. All three regions formed “nationhood” under the Le Kings, representing the “Golden Age” of Vietnam –- the Le Dynasty was founded by Le Loi (Emperor Le Thai To), who, aided by the renowned Mandarin Nguyen Trai (recognized by UNESCO as “Great Man of Culture,” part of World Heritage), had expelled the Ming Dynasty’s rulers from Dai-Viet. Governance and education under French occupation, therefore, served to fortify and cleverly exploit such North-Central-South historical division rooted in the chronology of Vietnamese nation-building.

The Indochinese Union was created in 1887, but its unity was only realized in 1898 by Paul Doumer, Governor-General of Indochina from 1897 to 1902. It consisted of five states: Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkin, Laos, and Cambodia, together with a territory ceded by China: Quan Tcheou on the Lei Tcheou peninsula, marginally to the north of the Hainan Straits.

(6) Cochinchina: This was the name of a French colony (formerly Southern Vietnam) made part of the Indochinese Union The colony was placed under a local Governor, whereas the other four states of Indochina were French protectorates, each headed by a French Resident Superior. The five-state Union was governed by a French Governor-General, and had its own administration and budget under the French Empire.

Under the Code de l’lnstruction Publigue (Code for Public Education), all five states of Indochina supposedly followed the same pattern of education, the so-called Franco-indigenous educational system, and shared a common university: the Indochinese University founded in Hanoi in 1907. Each state had a local service of education headed by a local chief, and the whole system of education in the Indochina Union was placed under the Director General of Public Education (Directeur Général de l’Instruction Publigue).

One major difficulty involved in any study of Vietnamese education under French occupation is the fact that French administrators compiled statistical data for Indochina as a whole, without further refining data into geographical or ethnic subdivisions. The researcher, therefore, must scout for distinguishing and integrating external facts and non-statistical data based on, inter alia, interpretations and cultural knowledge.

V. IMPORTANT DATES THAT CARRY BOTH HISTORICAL AND “EDUCATIONAL” SIGNIFICANCE:

The five dimensions of the scrutiny should also be played out against a historical backdrop that created two important “educational” dates, as explained below.

The Treaty of 1862 was signed on June 5, 1862, by the Emperor of Vietnam under which Vietnam ceded to France the fort of Saigon and the three Eastern provinces of Southern Vietnam, later named Cochinchina. This date marks the beginning of French colonial installation in Vietnam and hence was selected as the logical starting point for the five-dimension scrutiny.

French domination ended with the Japanese coup d’etat in Vietnam on March 9, 1945. Though the Japanese had virtually occupied Vietnam since 1941, the French colonial administration was allowed to continue their nominal rule until 1945. With the coup, the Japanese publicly proclaimed the end of French domination in Vietnam. Two days later, the Royal Court in Hue renounced the 1884 Protectorate Treaty and reclaimed Vietnam’s sovereignty. Emperor Bao Dai issued a Royal Edict as to his imperial governance on March 17. However, subsequent political events caused the Emperor to abdicate in favor of a provisional government led by Ho Chi Minh, who proclaimed the independence of Vietnam on September 2, 1945.

While President Ho Chi Minh was organizing his new government in Hanoi, the French returned to Saigon and, with assistance from the British, they seized this city on September 23, 1945, and thus started a new phase in Vietnamese history: the Franco-Vietnamese war (also known internationally as the Indochina War). This war ended in 1954, with the partition of Vietnam into two zones under the Geneva Convention in 1954. Ho Chi Minh’s troops (the “Viet Minh”) had declared victory for Vietnam with the 1954 battle of Dien Bien Phu.

For the schoolchildren of Vietnam during such a critical historical time, French colonial education ceased to exist in Vietnam as of 1945: French was no more the official medium in schools, and the whole education system fell into the hands of Vietnamese administrators.

Hence, the years of 1862 and 1945 are not only political and historical dates, essentially, but they also carry much significance in the study of educational systems. These years had “educational” meaning and should be used as landmarks for any study of education in Vietnam during the French occupation.

As explained earlier, traditional Confucian methods of instruction remained in Vietnam until 1919, the date of the last Confucian examination held in Annam. After that, Confucian Education was abolished by the French Governor-General at the time: Albert Sarraut, an advocate of mission civilisatrice. (A famous secondary French school in Tonkin was named after him, from which many famous Vietnamese licensed professionals, artists, scholars, and politicians graduated).

Accordingly, for his scrutiny into education, this author divides French occupation into two major periods: (1) 1862-1919, the predominant period of traditional Confucian Education; and (2) 1919-1945, the predominant period of Franco-Vietnamese Education. The year of 1884, marking Annam and Tonkin as French protectorates, was chosen to account for the beginning of the unique Franco-Vietnamese Education in these two territories (unique in the sense that:

it joined together two specific cultures, two different languages, of opposite nature, against the backdrop of an obsolete, made-dormant Confucian culture of a thousand years;

it was specially designed by the dominant culture — the rulers — for the subordinated culture – the indigenous subjects of an artificial political entity;

Franco-Vietnamese Education was a product geared specifically toward the native Vietnamese of the 20th Century, who reaped its benefit, while French occupation, although a reality, had never been fully accepted by the learning public for whom the product was designed; and

Practically, Franco-Vietnamese Education provided the framework and basis for the educational system of the Republic of Vietnam, i.e. South Vietnam (1954-1975). South Vietnam’s educational system was being further developed under an American model during its short 20-year lifespan when the Republic went defunct as a result of the Communist victory of 1975.

VI. FINDINGS BASED ON THE MULTIDIMENSIONAL SCRUTINY: The economic objectives versus “mission civilisatrice”

The more detailed actual scrutiny and documentation thereof are copyrighted material in book form, with limited distribution, on file with Southern Illinois University. The voluminous, detailed data and discussion do not permit a full summary herein, considering the scope and space of this article. However, this author’s findings are presented below. From the investigation conducted under the five dimensions, this author unfolds ten underlying facts, byproducts, and motivations that constituted the governing parameters for, and characterized French colonial education in Vietnam:

1) the need for immediate communication with native inhabitants, and the role of interpreters;

2) the need for training administrative collaborators;

3) the shrinking role of Chinese characters as the means of education (which ultimately led to the elimination or devaluing of Confucian ethics, consequently replacing them with French acculturation as the basis and structure of Vietnamese life – perhaps the very essence of “mission civilisatrice”);

4) the rising role of chu quoc ngu, the new written Vietnamese utilizing the Roman alphabet as the preferred (and ultimately mandatory) method of written communication and language of instruction;

5) French as the official medium of instruction for the highest upward mobility and for connecting Vietnam to the global environment, making French influence the focus of the new Vietnamese epistemology in the contemporary world;

6) Notwithstanding “mission civilisatrice,” there existed during French occupation a “horizontal” plan implementing the French policy of limiting and restricting education across the mass public. (This premise did not result from local geo – or socio -political factors including Vietnamese patriotism and indigenous resistance against French ruling, but, instead, was well-documented with empirical observations under the five dimensions described above.);

7) There existed further the use of examinations as a method to restrict education and to eliminate candidates;

8) high drop-out rate;

9) high rate of illiteracy; (the seventh, eighth, and ninth premises also confirmed the obvious byproduct of colonial education: those who passed these rigorous examinations and finished the intensive vertically structured of education at the top must-have survived this “horizontal” elimination plan; they therefore truly represented the new intellectuals of Vietnam, the “cream of the crop,” so to speak); and

10) higher education was motivated by centralized or “offshore” colonial politics that did not include local input or reflect local desires and aspirations.

VII. CONCLUSIONS: conflict between colonial economic objectives and the ideals of “mission civilisatrice” that should characterize any educational system

Based on the ten findings described above, this author makes the following conclusions:

The five-dimension scrutiny reveals three basic policies, purposes, and principal characteristics of French colonial education in Vietnam:

1) systematic economic exploitation of local talents and human resources, with defined goals of acculturation, rewards, and, therefore, control over collaborators and recipients of education.

2) structured and systematic training and production of cadres for the colonial administration, and

3) purposeful acculturation based on the French culture as the dominant culture to replace both Chinese influence and the indigenous way of life and thinking process.

The five-dimension scrutiny also reveals the following six major characteristics and common denominators that underlie the three co-existing patterns of education constituting the first (horizontal) dimension summarized above.

All three patterns of education — Confucian Education, French Education (where made applicable to the “privileged few” of the indigenous population), and Franco-Vietnamese Education — were highly competitive and rigorously eliminative. (The Confucian Education system, although officially terminated in 1919, remained as part of the integral family system essential to Vietnamese life, and were perpetuated via exposure to ancient creative literature and an individualized “tutoring” system resulting from the family structure.)

All three patterns provided routes to public services and governmental positions, as part of the overall colonial regime. (At the same time, these patterns also helped create a new class of wealthy and property owners: the urbanites, the small business owners, the petit bourgeois, the few yet existing Vietnamese industrialists, and of course rice farmers-landowners who could afford to send their children abroad, primarily France, for further schooling. Dedication to and value placed on learning was not just the product of French acculturation, but instead, the result of more than a thousand years of Confucian ethics via the old system of self-imposed duty and upward mobility based on Chinese proficiency. (quoting Mandarin Nguyen Cong Tru: “Da mang tieng o trong troi dat, phai co danh gi voi nui song” trans: “being born into in this universe of Heaven and Earth, I must leave a reputable name with rivers and mountains.”)

All three patterns of education were designed to favor and perpetuate a class of privileged elites, separating the privileged from the common people of the agricultural and artisan/small business societies.

All three patterns emphasized the either Chinese or French language and culture, instead of the indigenous Vietnamese culture. (Nonetheless, the family system, as well as the “village” system and a wealth of folklore oral literature perpetuated the indigenous values and ways of life, including the sense of “community,” “history,” and “country.”)

All three patterns stressed literary education to the detriment of vocational and technical education, perpetuating, therefore, a high number of the bottom-rank “under-privileged” who remained impoverished superstitious, and illiterate; and

All three patterns encouraged memorization and imitation, at the expense of initiatives or creativity in problem-solving. However, with language proficiency as the inroad to the communication of thoughts and ideas, the emphasis on memorization and imitation could not block or hinder the curiosity and absorption of the Vietnamese “elites,” leaning toward exposure to learning from sources outside Vietnam. “Subconscious” indigenous values via existing “family” and “village” systems, therefore, remain the highest competition force against “consciously applied” French acculturation via the training of colonial cadres and the educated elites.

VIII. EXPOSITORY COMMENTS – the historical context versus present inquiries

Any study on French education in Vietnam must cover almost a century of the French occupation: from 1862, the year of the Treaty of Saigon, to 1945, the year of the Japanese coup d’état and Ho Chi Minh’s Declaration of Independence in Hanoi, followed by Emperor Bao Dai’s abdication speech given in the Imperial City of Hue. However, the French quickly returned to Vietnam. The Indochina War between the French and Ho Chi Minh’s Resistance Troops (the “Viet Minh”) lasted from 1945 to 1954. The Geneva Convention finally signaled the end of French colonialism, only for the Vietnam War (1954-1975) to erupt, making America a player in what appeared to be a devastating civil conflict. Ideologically motivated, the Vietnam War became parallel to, and an integral part of, the international Cold War.

According to Britannica, the “Viet Minh” as of 1945 was couched as a national movement aiming for independence and decolonization of Vietnam, open to all Vietnamese regardless of political inclination or affiliations.

The Treaty of Saigon (signed in June 1862 by Emperor Tu Duc and ratified by him in April 1863), achieved France’s initial foothold in Vietnam. The Treaty gave France the three Eastern provinces of Southern Vietnam, the agriculturally richest part of the country (ultimately given the name of Cochinchina by French colonists). The Treaty also secured for France the opening of three ports to trade, freedom of missionary activities, protectorate power over Vietnam’s foreign relations, and an imposition of a large cash indemnity or compensation to be paid to France by the Vietnamese sovereignty.

The chief negotiator of the Treaty of Saigon, Mandarin Phan Thanh Gian, ceded Gia Dinh and Dinh Tuong in hopes that the French would stay out of the remainder of Vietnam. Yet, five years later, France annexed the rest of Cochinchina, turning it into a French colony. A Treaty of Protectorate, signed at the August 1883 Harmand Convention, established a French protectorate system over Northern and Central Vietnam, effectively ending Vietnam’s independence as a nation-state. In June 1884, Vietnam signed the Treaty of Hue, which confirmed the Harmand Convention agreement. By then, the French occupation of the entire country of Vietnam was formalized and complete.

In the words of contemporary Western historians, colonialism was the political-economic mechanism whereby various European nations explored, conquered, settled, and exploited resources of the lesser developed word (“lesser developed” in the sense of 19th and 20th-century technology, but not necessarily in terms of anthropological, historical, and cultural identity.)

Put differently, from the perspective of the indigenous cultures, colonialism was not just the political and economic conquest of their native land – an act of robbery, but also a deeply inflicted emotional wound that offended and destroyed their identity.

Acculturation, therefore, was part of the painful exchange of land control for gradual exposure to, and acquisition of, a different lifestyle more in line with modern technology and global travels, which ultimately led to global education. Education and acculturation thus became the “incidental benefit” of that painful and bloody exchange, beautified into the “mission civilisatrice” of the developed world.

The age of colonialism dated back to 1500, with the European discoveries of a sea route around Africa’s southern coast in 1488, and of America in 1492. Thus, colonialism came about as the result of a very long process, which involved advancement in sea-going technology and naval power. So, the less fortunate nations of Asia and Africa could have avoided colonialism had they invested in preparation for technological coming-of-age and advancement to achieve a level-playing field, in order to benefit from the mutual economic (and cultural) exchange that drove colonialism.

In Vietnam, this wisdom of mutual economic exchange was effectively achieved during the era of Lord Nguyens’ rulings over Central and Southern Vietnam, beginning approximately around 1558. (The first Lord Nguyen, Nguyen Hoang, was an official of the Le Dynasty, who escaped the internal politics of Northern Vietnam by seeking the Le Emperor’s permission to embark upon a mission of “southern expansion and development.” Leading willing immigrants, Nguyen Hoang moved south to establish the era of “Nguyen Lords,” thereby creating a Southern territory separate and independent from the North (controlled by the Trinh Lords who established protectionism over the Le Dynasty).

The wisdom of the various Lord Nguyens’ international trade and mutual economic exchange in the Southern territory was evidenced by the continuing development and prosperity of the port town Hoi An in Central Vietnam, one of Vietnam’s very first coastal international trade centers. Yet, Hoi An declined in subsequent centuries due partly to civil wars. In 1802, the Nguyen Dynasty was finally established in the honor of the previous Lord Nguyen’s in order to close the ‘civil war’ chapter and to unify the country. The Nguyen Dynasty, the last of Vietnamese monarchs, modeled Vietnam after the isolationism of China, and had to fight losing military battles against the French invasion.

French invasion, therefore, was a nasty, bloody tragedy, as demonstrated by, inter alia, historical documents written by French officers and soldiers, describing their passionately stabbing the weaker Vietnamese soldiers in one-to-one combat on the beach of Thuan An port, which guarded the Vietnamese imperial city of Hue. In the history of Vietnam, the massacres of Hue must therefore include, not only (i) the imperial uprising of Mang Ca in 1885, which led to the “Can Vuong” [Assisting-the-Emperor] anti-French resistance movement, and (ii) the famous-infamous Tet Offensive of 1968 during the Vietnam War, but also (iii) the rarely-discussed battle of Thuan An in 1883, where thousands of Vietnamese imperial soldiers were slaughtered in the defense of their homeland against sea-going navy Frenchmen. Casualties to France during the battle of Thuan An were reportedly minimal.

Imagine what it was like for Vietnamese students and scholars to sit through “Confucian Education” and “Franco-Vietnamese Education” rigorous systems after and during such time of brutality, bloodshed, chaos, and humiliating challenges both to ethnic identity and cultural loyalty?

In France’s vision of its presence in Vietnam, by 1857, Louis-Napoleon preferred military invasion as the best course of action to advance French interest. Hence, French warships were instructed to take Tourane (now known as the port City of Da Nang in central Vietnam), without further negotiation with the native imperial government. Tourane was captured in late 1858; however, Vietnamese resistance and outbreaks of cholera and typhoid forced the French to abandon Tourane in early 1860. Meanwhile, Paris feared that if France gave up, the British would move in. Also current in Paris at that time (and thereafter) was the rationalization that France had a “civilizing mission” to bring the benefits of its superior culture to the less fortunate lands of Asia and Africa. (This was the common “goodwill” justification for most of the Western countries practicing colonialism, and not just France.)

Yet, in 1930, French colonists guillotined the 13 young men of the newly formed Vietnamese Nationalist Party, who plotted a military coup against the French. The guillotine sent a very clear message of capital punishment that obviously demonstrated no goodwill. Many, if not all, of these 13 young men and their followers were products of the type of colonial educational system and administrative governance described by the author of the five-dimension study. Apparently, the message from the French was that education took place as part of the French mission to civilize, but only to produce the “obedient” who would not touch the guns.

A fortiori, the paradox that lies between such self-serving “mission civilisatrice” and the “rule-by-force doctrine” was manifested in the colonial educational systems investigated by the author of the five-dimension study. His findings and conclusions as summarized in this article were perhaps the best testament of this paradox, thereby affirming that “mission civilisatrice” was lip service to justify and camouflage economic exploitation and

political control. Colonial educational policies and practice were naturally toward the oppressive end.

Yet, the indigenous natives did benefit from such educational system, despite its rigid standard and eliminative objectives (e.g., the five-dimension author made reference to the “restrictive horizontal plan” applicable across the general Vietnamese populace). Such elimination goal further deepened the gap between the few “vertical” native “elites” versus the “horizontal” mass public.

In the 2000-year official history of Vietnam, almost all Vietnamese ruling dynasties had had to engage in, and exhibit adroitly, a consistent level of Vietnam’s humbling vassalage toward China (i.e, “co-existence” with admitted inferiority, as distinguished from civilized superiority), even after Vietnamese resistance had defeated Chinese invasion.

It followed, therefore, that, in hindsight, a soul-searching question must be raised by the indigenous patriots as well as historians: whether a wise geo-political policy of “co-existence” between the indigenous culture and the colonists might have been a better long-term solution to stop or end colonialism at its roots, without the bloodshed, casualties, and destructiveness of resistance wars. (By the mid-20th century, territorial conquest had been outlawed under public international law, and nationalism/decolonization had become a global geo-political trend. Hence, other international legal theories must be invoked to justify the territorial invasion, for example, the “preemptive strike defensive war” doctrine used to justify the war initiated by the United States in the Middle East in the 1990s).

One can also assert that all historical perspectives and evaluations are products of hindsight: possible construction and deconstruction of present impressions and evaluations about a past that is gone, a “fait accompli.” Theoretically, all such established past, i.e., History, could have been altered under a well-reasoned, well-structured “retroactive” hypothesis. The benefit of such a History-based hypothesis is only to benefit policymakers of the present and the future — the lesson learned from hindsight experience, applied under a different set of geopolitical considerations. A past re-cast is the past deconstructed into a hypothetical past.

Last, but not least, today, one must also look more closely at late 20th- and 21st-century “globalization” –- whether international trade and foreign direct investment also share certain common characteristics with the illusory “civilizing-while-colonializing” rhetoric of the colonistic past. Sadly, such rhetoric still exists today in internationalists’ terminologies: the “developed” nations versus the “developing” nations. Oh yes, many nations are “developed,” but others remain “developing,” and all nations thrive on, and strive for, this ladder of “development.” In what sense or semantics is such “development” viewed and voiced?

Sadly still, in documenting and evaluating past educational systems as part of historiography, one encounters the specter of nations that no longer exist. For example, on the peninsula of French Indochina, there was once the Kingdom of Champa. What kind of educational system did the Chams get, if any, from the Vietnamese, who took the Chams’ land, compared to what Vietnam received educationally from France, who later occupied Vietnam?

As another example, today, we have China, and then we have Tibet. Does Tibet still legally exist? Perhaps yes, under certain interpretation of public international law, taking the perspective of the Dalai Lama and his people. But, under the Third Restatement of Foreign Relations of the United States (American jurisprudence on the definition of “nation”), there is no “statehood” or “nationhood” unless there are three established elements: People, Territory, and Government. Does Tibet still have Territory? It does, as the land of Tibet is still there, although the people of Tibet living in exile cannot claim control over such land. Yet the culture of Tibet (and, therefore, its people’s notion of “statehood”) still exists, without borders, of course. In their daily existence, the land still belongs to the exiled Tibetans, in their concept of nationhood or statehood. Do the exiled Tibetans still have a Government? Perhaps yes, because the Dalai Lama represents the exiled Tibetan people’s “sovereignty.”

What’s more, for those Tibetans who currently live in China, what kind of “educational system” have they received, if at all?

***

I want to use this China-Tibet analogy to pay tribute to the tireless works of scholars such as the five-dimension author in their studies of past educational systems that took place on the land of the oppressed. It was their land, but whose educational system was that? History supposedly gave us the answers, the pros and the cons, because the lip service of “mission civilisatrice” did have its byproducts. Education was bestowed by the new rulers, thereby producing scholars and intellectuals who hoped to lead and free their people. In hindsight, perhaps such leadership might not always have to be the battlefields.

Last but not least, how do studies of the past, especially in the field of education, aid the present? A question to be confronted by responsible policy-makers.

We came to individual opinions, as students, teachers, and readers of the 21st Century, through works such as the five-dimension approach presented above.

And more.

©Wendy Duong Nhu Nguyen

Friday, February 25, 2022

tho, cu va moi

THƠ CỔ

VÀ THƠ MỚI ©dnn2022

Cổ Thi không phải là thơ cũ

Bạn Cũ vào xem, Mới

mới ra

Mới ra, ra Mới, không là Mới

Cũ vào, không Cũ, M/mới là Ta

Con bé năm nao mê đọc sách

Bà lão hôm nay, lệ nhạt nhoà

Xin trả tôi về bên gối Mẹ

Vòng xe Bố đạp, tháng ngày qua

Tiếng Việt trong tôi là thế giới

Cuốn giữ tôi bằng chiếc chiếu hoa*

Beethoven nhớ tôi

hay nhớ

Tiếng đàn Sonate

cuả cung Fa**

Để tôi được sống vào muôn thuở

An nghỉ nghìn thu, buổi tịch tà

*Doãn Quốc

Sỹ

**Sonatina in F major, Ludwig Van Beethoven

Wednesday, February 23, 2022

Saturday, February 19, 2022

LE HAI BA TRUNG

2/19/2022

Saturday, February 12, 2022

among my favortie's by Chopin

Thursday, February 10, 2022

In the arena of Vietnamese literary critiques and Vietnamese literary studies

1 Comment

NOI VE CONG TRINH BIEN KHAO CUA BA CONG HUYEN TON NU NHA TRANG VE VAN HOC MIEN NAM:Active

Wendynicolenn Duong

VietHai Tran MinhNgoc Nguyen Nhã-Văn Đoàn qua ban ron nhung phai len tieng. V/d vo ly: Ba Nha Trang viet bai nay, toi co doc mot phan: tieu luan cham dut khoang thoi gian nghien cuu la nam 1975 thi lam sao co viec ba noi len nhan xet ve nhung Le Thi Hue, Tran Dieu Hang, Pham Thi Ngoc, nhung nguoi ve sau nay: TDH va LTH van phong but phap va cau truc rat kem va khong co tinh chat tieu thuyet that su vi cot truyen guong ep, khong the dem so sanh voi nhung nguoi di truoc duoc, vi do la nhung tieu thuyet gia dung nghia. Do chac chan phai la phan ma nguoi khac them vao, vi bai viet cua ba Nha Trang nham vao khoang thoi gian cham dut o 1975. Nguoi nao viet bai nay coi thuong doc gia: doc gia khong qua ngu dot de khong nhan thay su vo ly nay. De tua cua bai khao cuu xac dinh thoi gian ti'nh: cham dut o 1975, ma bai tom tat thi noi den Post-1975??? Them nua, hinh nhu bai cua ba Nha Trang la mot phan luan an cua ba o Berkeley. Dieu nay toi phai xem lai, cho nen toi du`ng chu "hinh nhu" chu khong noi chac chan Trong giai doan truoc 1975, sinh vien di hoc Viet Hoc o My rat it cho nen ba Nha Trang co cho du'ng dac biet, dieu do khong co nghia rang ba Nha Trang la nguoi doc nhat viet ve khao cuu van chuong tieng Viet. Bay gio thi khac roi. Rat nhieu nguoi khac da ra doi ma cong dong nguoi Viet khong biet den. Ba Nha Trang la nguoi quen cua gia dinh toi, goc hoang toc o Hue. Toi hieu cai nhin cua ba rat ro, va dong y voi ba nhieu diem. Toi khong tin la cong trinh khao cuu cua ba tu nhien lai moc them cai duo^i: noi ve nhung cay viet tu phong (self-proclaimed) nhu LTH va TDH. Toi hoc chung truong voi ba TDH o VN. Toi biet van chuong cua TDH nhu the nao ngay tu thoi so khai. TDH khong sanh duoc voi mot tai nang khac cua truong nu trung hoc TV: mot tieu thuyet gia dung nghia: Nguyen Thao Uyen Ly. TDH va LTH khong phai la tieu thuyet gia, theo mat nhin cua toi, vi cot truyen va nhan vat vo cung guong ep. Giua xu mu anh chot lam vua trong thoi diem thieu nhan tai. Sorry, I know what I am talking about, and I am intelectually honest. I did scholarly work myself, so I understand what literary research and literary analysis, literary critique are all about. DNN .